The Bauhaus was one of the most influential movements in modern art, architecture, and design, and its brief yet dynamic history unfolded across three German cities: Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin.

*At the Bauhaus in 1927 or at a Raincoats gig upstairs at The Chippenham in London in 1979? You choose.

Bauhaus in Weimar

Weimar holds a special place in the history of modern design as the birthplace of the Bauhaus. Founded in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus began as an ambitious experiment in redefining art, architecture, and design education. It sought to merge fine art with craftsmanship, breaking down the traditional hierarchies between artist and artisan. During its formative years in Weimar, the Bauhaus laid the theoretical and artistic foundations that would later influence generations of architects, designers, and educators across the globe.

Housed in the former Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts, the early Bauhaus attracted a range of pioneering artists, including Johannes Itten, Lyonel Feininger, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky. The curriculum combined workshops, theory, and experimentation, with an emphasis on unity between function and aesthetics. While the Weimar period was marked by creative innovation, it also faced political opposition from conservative forces who viewed the school as too radical. Ultimately, this tension led to the Bauhaus being forced out of Weimar in 1925, when it relocated to Dessau.

Today, the legacy of the Bauhaus remains deeply embedded in Weimar’s cultural identity. The original Bauhaus building on the campus of what is now the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar has been preserved and restored. In 1996, it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the Bauhaus buildings in Dessau. The university continues the school’s educational legacy, offering programs in architecture, design, media, and the arts, echoing the interdisciplinary spirit of the original Bauhaus.

In addition, the Bauhaus Museum Weimar, reopened in 2019 to mark the centenary of the school’s founding, showcases a huge collection of artifacts, furniture, documents, and artworks from the early Bauhaus period.

Whilst in Weimar, take a look at the Hotel Elephant and its Bauhaus legacy in the main square. The hotel became an informal gathering place for many Bauhaus artists and intellectuals. Though not designed by Gropius himself, the hotel’s modernist renovation in the 1930s reflected the aesthetic ideals championed by the Bauhaus, making it a symbolic extension of the movement’s presence in the city.

The current incarnation of the Hotel Elephant combines modern luxury with a reverence for the city’s past. Originally established in the 17th century, the hotel has undergone several transformations, the most significant of which occurred in the early 20th century, aligning it with the radical vision of the Bauhaus. When the movement was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919, the city became a nexus for revolutionary ideas in design and aesthetics. The Hotel Elephant, located just steps away from many of the cultural institutions that supported Bauhaus ideals, naturally became a meeting place for many of its leading figures.

What makes the Hotel Elephant’s connection to Bauhaus more than incidental is its embodiment of the movement’s principles: clarity of form, functionality, and the integration of art into everyday life. The hotel’s modernist redesign in 1938 reflected Bauhaus-inspired sensibilities, emphasizing clean lines, geometric shapes, and a harmonious blend of materials.

Among its most famous guests was the playwright Bertolt Brecht, himself influenced by the intellectual currents of Bauhaus and modernist theory. The hotel also served as a gathering point for other avant-garde thinkers and artists who shaped the cultural fabric of the early 20th century.

The design of the ground floor of the hotel is a seamless combination of art and comfort. At its heart is the Lichtsaal, a light-filled lounge where velvet-upholstered armchairs, leather sofas, and polished parquet floors create an inviting, living-room atmosphere. The walls are adorned with a carefully curated art collection featuring works by early Modernists such as Lyonel Feininger, Max Beckmann, and Otto Dix, alongside contemporary pieces that reflect Weimar’s rich artistic legacy. Drawing inspiration from Goethe’s Theory of Colours, the interior palette fuses muted greys, deep blues, and emerald tones with Art Deco accents, evoking both intellectual depth and visual warmth.

The hotel is indeed a stylish tribute to the Bauhaus.

Bauhaus in Dessau

In 1925, following political pressure in conservative Weimar, the Bauhaus relocated to the city of Dessau in Saxony, where it entered its most productive and internationally influential phase.

Contemporary Dessau is a modest-sized city with a population of just under 80,000. While it was heavily damaged during World War II, its postwar reconstruction included both modernist housing and socialist-era architecture. Today, the city is known primarily for its Bauhaus heritage, which attracts thousands of visitors and architecture students from around the world.

In Dessau, the Bauhaus found a more industrially supportive environment, aligning with the city’s aspirations to become a center of modern industry and innovation. Gropius designed the new Bauhaus building, completed in 1926, as a radical embodiment of the school’s ideals. It featured a striking glass curtain wall, asymmetrical layout, and open interiors that emphasized light, transparency, and functional design. The school operated here until 1932, when it came under increasing political pressure from the Nazi regime, leading to its move to Berlin and eventual closure in 1933.

During its time in Dessau, the Bauhaus school attracted some of the 20th century’s most important artists and designers. Among them were Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, and Josef Albers, who served as masters and developed experimental and interdisciplinary approaches to teaching art, architecture, typography, and product design. The Bauhaus became known for its revolutionary educational model and its efforts to integrate art with modern technology and everyday life.

In addition to the school building, Gropius designed a series of residences known as the Meisterhäuser (Masters’ Houses), built for the school’s leading faculty. Located near the school, these duplex and single-family homes exemplified Bauhaus architecture through their clean lines, flat roofs, geometric forms, and minimalist interiors. Each house was designed as a modular space that could accommodate both living and working needs, further embodying the school’s emphasis on functional design.

Despite war damage and postwar neglect, efforts to preserve and restore the Masters’ Houses began in the late 20th century. Some original buildings were reconstructed or rehabilitated using historic plans and photographs, while others, notably the Gropius and Moholy-Nagy houses, were reinterpreted as abstract volumes to reflect their destruction during WWII.

To better preserve and present the legacy of the movement, the Bauhaus Museum Dessau opened in 2019, coinciding with the Bauhaus centenary. Designed by the Spanish architecture firm addenda architects, the museum is a minimalist structure of steel and glass that reflects Bauhaus ideals while also serving as a contemporary cultural hub. The museum houses over 49,000 objects, making it one of the world’s most significant collections related to the Bauhaus. Exhibitions explore the school’s history, its pedagogical experiments, and its ongoing global influence on modern design and architecture.

Bauhaus in Berlin

The Bauhaus was forced to close in Dessau in 1932 due to increasing political pressure from the rising Nazi regime. The school moved to Berlin for what would become its final and most difficult phase.

The move to Berlin was spearheaded by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who had taken over as director of the school in Dessau in 1930. In Berlin, the Bauhaus no longer had public funding or official institutional support, so it reopened as a private school in a disused factory building in the Steglitz district. This final phase marked a shift toward a more architectural and less craft-based focus under Mies’s direction.

However, the school’s time in Berlin was short-lived. The Nazi regime viewed Bauhaus as a breeding ground for what it called “degenerate art” and a haven for leftist and internationalist ideas. In April 1933, only a few months after Hitler came to power, the Gestapo raided the Berlin school. In response to increasing harassment and pressure, Mies van der Rohe and the other faculty members voted to voluntarily dissolve the Bauhaus in July 1933.

Although the physical school ceased to exist, the Bauhaus movement continued internationally. Many of its key figures fled Nazi Germany and emigrated to countries such as the United States, the Soviet Union, and Palestine.

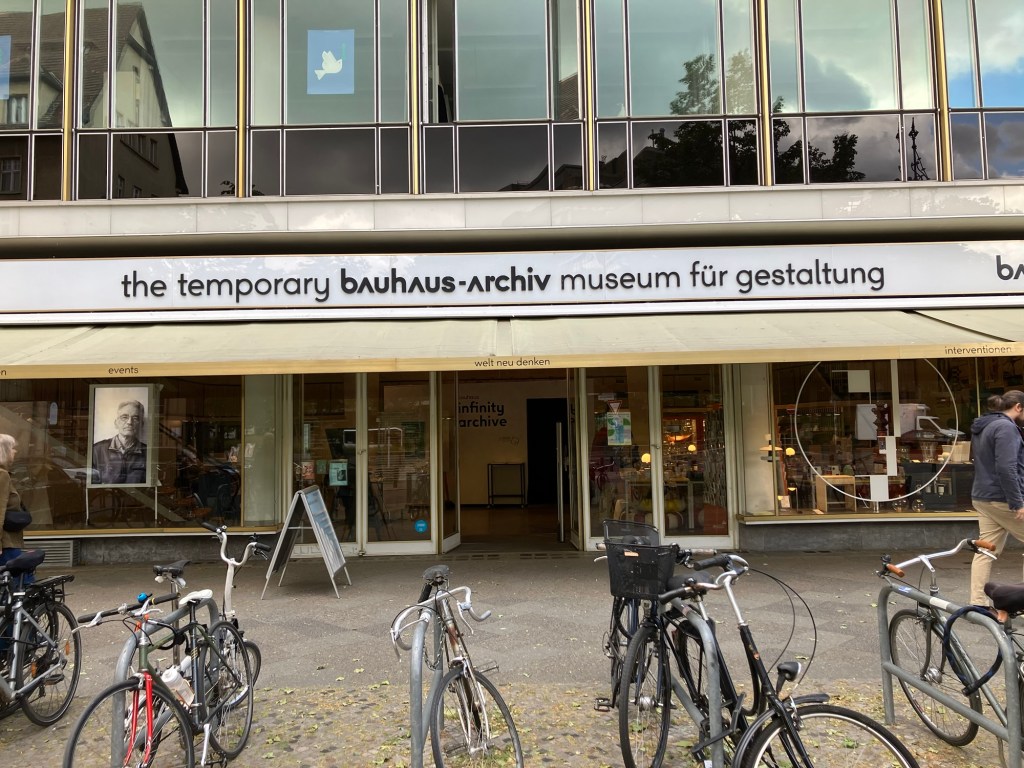

The Bauhaus presence in Berlin today is in a state of transition. Whilst the main Bauhaus‑Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung is undergoing renovation and expansion, a temporary venue has been opened at Haus Hardenberg, located on Knesebeckstraße in the Charlottenburg district. This small, interim space serves as a pop‑up exhibition site, bauhaus‑shop, and event venue, highlighting collections related to design, architecture, and contemporary issues.

After visiting the temporary bauhaus‑archiv we made our way down Hardenbergstraße, past the elegant facade of the Renaissance-Theater to the Zoologischer Garten station for lunch. Forget the regrettable Curry Wurst, a Dőner Kebab beckoned. If the Bauhaus is one of the country’s major cultural achievements, the Dőner Kebab is undoubtably one its culinary icons. With over 1600 outlet’s citywide, Berlin is widely considered the birthplace of the modern Döner Kebab sandwich, thanks to Turkish immigrant Kadir Nurman, who began selling it in the 1970s at West Berlin’s Zoologischer Garten station.

The Döner Kebab has taken distinct forms in the UK and Germany, each reflecting the culinary habits, cultural histories, and migration patterns of their respective societies. While both serve as a popular form of fast food, their reputation and quality diverge significantly.

In the United Kingdom, the typical doner kebab is often seen as a late-night indulgence—greasy, heavily salted, and served from takeaway shops catering to post-pub crowds. The meat is frequently processed and reconstituted, shaved from a large cone of compressed lamb or beef, sometimes of uncertain provenance. It’s commonly served in pita bread with shredded lettuce, raw onions, and chili sauce, often dripping with fat and served with chips. For many in the UK, the doner is associated with hangovers rather than culinary satisfaction, and is frequently viewed as low-quality or unhealthy.

By contrast, in Germany, particularly in Berlin, the Döner Kebab has developed into a national street food institution, often praised for its freshness, quality, and variety. Typically made with marinated slices of veal, chicken, or beef (rarely lamb), the German Döner includes crisp vegetables like cabbage, tomato, cucumber, and onion, along with homemade sauces—yogurt-based, garlic, herb, or spicy chili. It’s usually wrapped in fluffy Turkish flatbread or Dürüm (thin lavash) and prepared to order. The emphasis is on balance and freshness, and many shops offer vegetarian and vegan options with grilled halloumi, falafel, or seitan. In Germany, the Döner is not just a snack, but a respectable, affordable meal enjoyed across all demographics.

We think that there are conceptual parallels between the Dőner Kebab in Germany and the Bauhaus. They both embody principles of modernity, functionality, and cultural synthesis, making them conceptually parallel in several striking ways.

The Bauhaus championed the idea that design should serve everyday needs. Its mantra, “form follows function,” emphasized simplicity, clarity, and usefulness. Similarly, the döner kebab—particularly as adapted in Germany—is a highly functional food. It’s designed for urban living: portable, efficient, and complete in one hand-held form. Like a Bauhaus object, it strips away unnecessary elements to focus on what works.

Both the Bauhaus and the German döner are also products of cultural fusion. Bauhaus design integrated ideas from multiple disciplines and cultures to create something universally modern. The döner kebab, created by Turkish immigrants and adapted for German tastes, is a hybrid of Middle Eastern tradition and European pragmatism—an edible symbol of cosmopolitanism.

Additionally, each reflects a commitment to mass accessibility. Bauhaus sought to democratize good design through industrial production; the döner is inexpensive and ubiquitous, serving everyone from students to workers. Both exist comfortably within the rhythms of modern, urban life.

Finally, their modular, repeatable nature underscores a shared design logic. Bauhaus structures were often modular and adaptable; the döner is constructed from standardized parts—bread, meat, salad, sauce—easily varied yet fundamentally consistent.

In essence, the German döner kebab and the Bauhaus share a conceptual foundation rooted in function, accessibility, modernism, and synthesis. One feeds the stomach, the other the senses—but both are crafted for the modern world.

Bauhaus was an essentially German creation and whilst the Dőner Kebab may have been greatly popularised and even conceived in German, it remains an essentially Turkish creation.

The nearest commercial food outlet to the Bauhaus campus in Dessau is the redoubtable ‘Enfes Dőner Kebab am Bauhaus’.