Leipzig is a city located in the eastern part of Germany in the state of Saxony. Although badly bombed during WWW2 and unsympathetically rebuilt under Soviet rule, it is still an attractive city, popular with visitors (especially classical music aficionados) as during the 18th and 19th centuries it was a centre of learning and culture, with famous composers like Johann Sebastian Bach, Felix Mendelssohn, and Richard Wagner all working in the city.

Bach is particularly associated with the city. He spent the last 27 years of his life in Leipzig, from 1723 until his death in 1750. During this time, he held the prestigious position of Cantor, or Directore Chori Musici Lipsiensis, which meant he was responsible for directing the choir and music in the city’s churches.

The Organ console from Johanniskirche, St. John’s Church, which Bach was known to have tested and played after its installation.

In addition to his work as Cantor, Bach was also a respected organist and harpsichordist. He was involved in the design and construction of several organs in Leipzig’s churches. In particular, St. Thomas Church (Thomaskirche) and St. Nicholas Church (Nikolaikirche) both have strong associations with Johann Sebastian Bach.

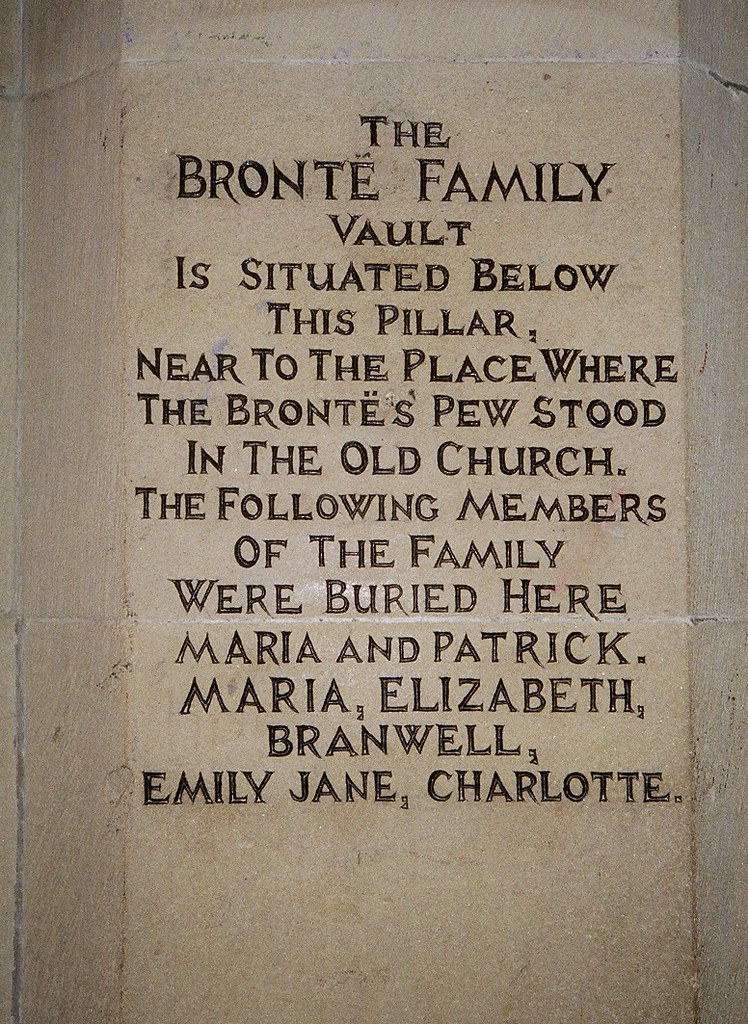

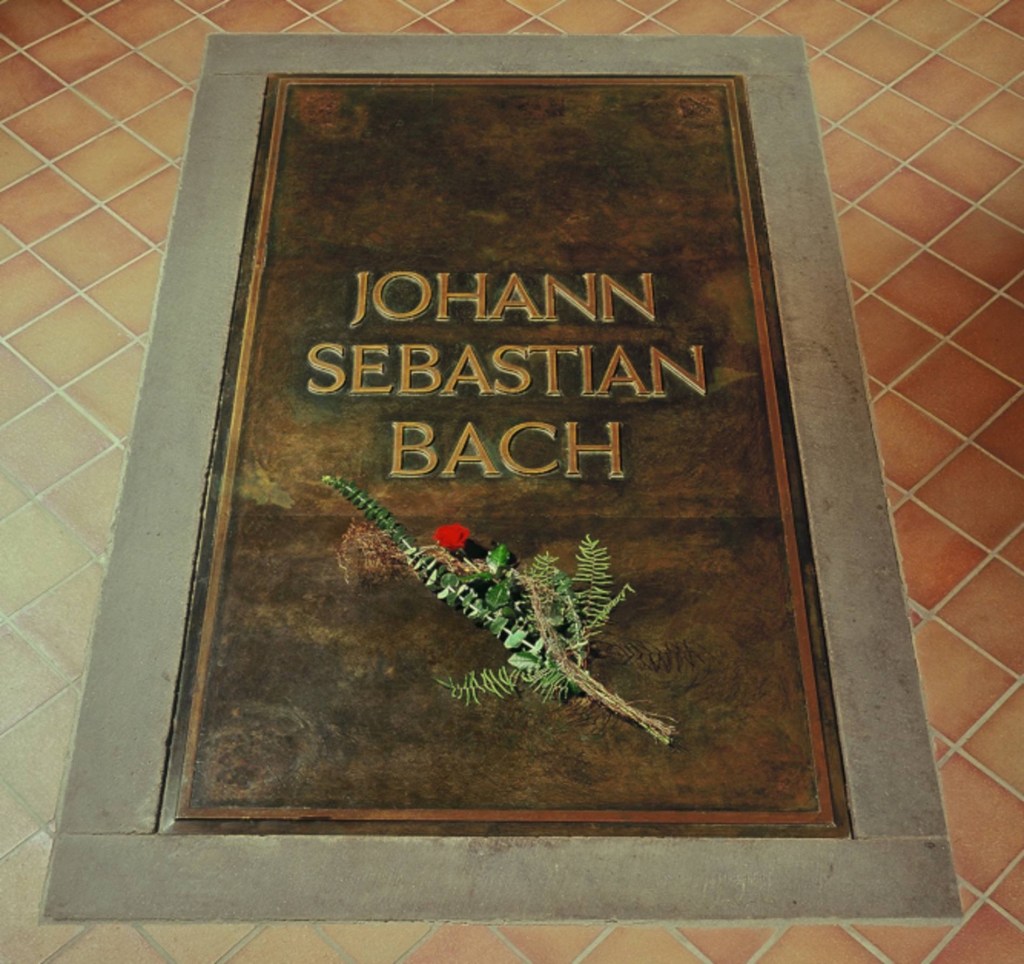

At St.Thomas Church, Bach served as the music Director (Thomascantor) from 1723 until his death in 1750. Many of his most famous works, including the St. Matthew Passion, were premiered at the church. He is buried in the church crypt and his grave is marked with his name as the sole inscription. ‘Joh. Sebast Bach’. The crypt was not the original resting place for his bones as his body was originally buried in an unmarked grave in the cemetery of St. John’s Church (Johanniskirche). The church , which was located just outside the city’s Grimma Gate, was destroyed by aerial bombing during WW2.

Over time, the exact location of Bach’s grave was lost, but in 1894, church officials decided to search for Bach’s remains during renovations at the church. According to local lore, Bach was buried “six paces from the south door of the church,” and excavators focused their search in that area. On October 22, 1894, diggers found a plot that matched the description and discovered Bach’s oak coffin, one of only twelve oak coffins buried at the church in the year of Bach’s death. The bones were transported in an open zinc casket on the back of a handcart to St.Thomas Church. The remains were later confirmed to be those of Bach through various analyses, and in 1950, 55 years after the discovery, Bach’s remains were reinterred at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, to commemorate his role there as Cantor.

However it was St. Thomas Church which was to play a key role in the protests against the Soviet controlled German Democratic Republic (‘GDR’) in 1989. The protests began in September 1989 with a weekly prayer service at St. Nicholas Church. Protesters gathered in front of the church and marched to Augustusplatz, where they held peaceful candlelit demonstrations to demand democratic reforms and the right to travel freely. These peaceful demonstrations, known as the “Monday demonstrations,” grew in size and intensity over the following weeks, with tens of thousands of people taking to the streets to call for freedom and democracy.

On October 9, 1989, the largest of these demonstrations took place, with over 70,000 people marching through Leipzig’s streets. The GDR security forces did not intervene, marking a turning point in the protests. Within weeks, the Berlin Wall fell, and the East German government collapsed.

Leipzig’s role in these events is often referred to as the “Peaceful Revolution” and is considered a key moment in the broader movement for freedom and democracy in Eastern Europe.

Leipzig played a crucial role in the fall of the GDR, as it was the site of peaceful protests that eventually led to the opening of East Germany’s borders and the end of communist rule.

Despite attempts by the East German authorities to suppress the protests, they continued to grow in size and spread to other cities across East Germany, leading to the eventual reunification of Germany.

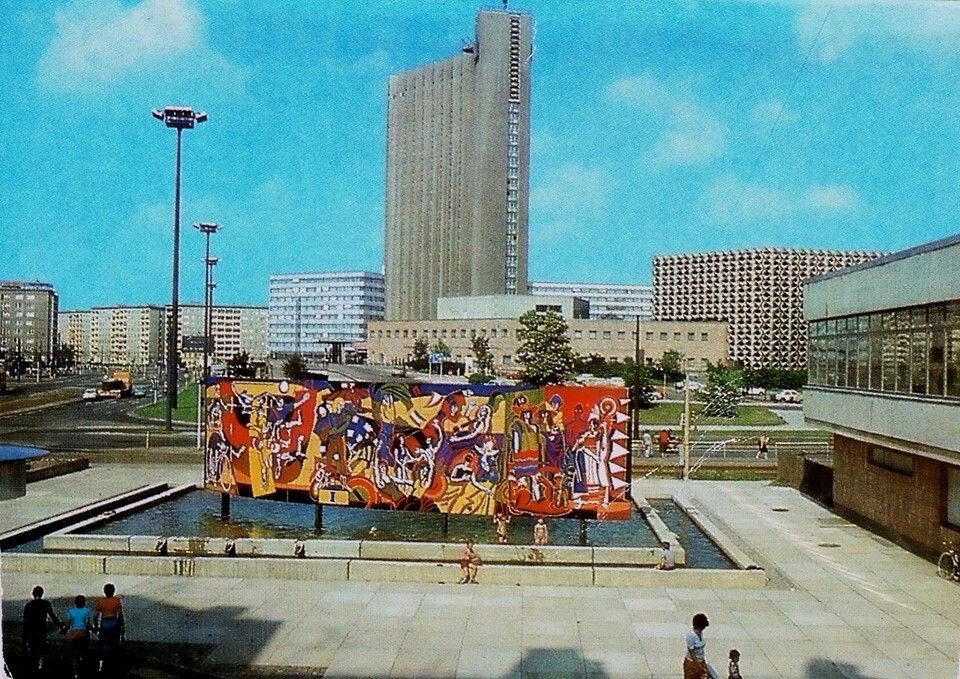

Those original protesters in September 1989 had headed away from St. Nicholas Church to Augustusplatz, the most important public space in Leipzig. The square is surrounded by a jumble of disparate architectural styles culminating in the monolithic Opera House which stands at the northern end of the square.

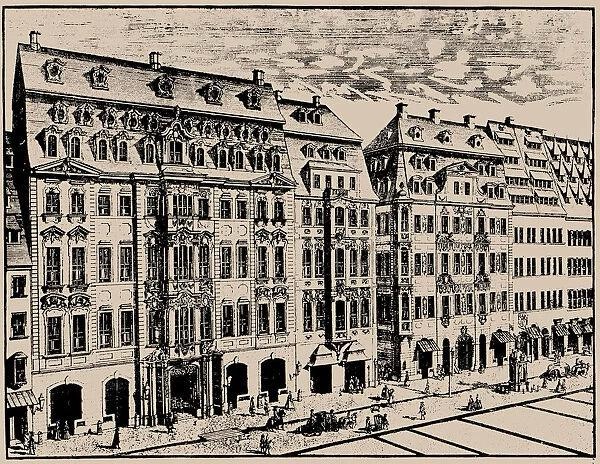

The history of the Leipzig Opera House is one of destruction and reconstruction. The original venue, known as the Oper am Brühl, was built in 1693 and opened its doors that year. Unfortunately, this original opera house was found to be in a dangerous state in 1719, leading to its closure in 1720 and demolition in 1729. A new venue was eventually built in 1842 (‘the Semperoper’) but this was destroyed by fire in 1869.

The original Leipzig opera house, known as the Oper am Brühl, was built in 1693 and opened its doors on May 8th of that year. Unfortunately, the original opera house was found to be in a dangerous state in 1719, leading to its closure in 1720 and demolition in 1729. It took a while for a new opera house to be built in the city, the Semperoper which was constructed in 1841 but destroyed by fire in 1869. A further opera house was created, the Neues Theater which served as the city’s premier music venue until it too was destroyed during the air raids of World War II in 1943.

The Neues Theater hosted many famous musicians and performers, including Richard Wagner, who premiered his opera “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg” at the theater in 1868. Other notable musicians who performed at the Neues Theater included Giuseppe Verdi, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and Johannes Brahms.

After the destruction of the Neues Theater during the war, it was not until 1960 that a new opera house, the current Leipzig Opera, was built on Augustusplatz.

The Leipzig Opera House was the only new opera building constructed in East Germany during the 41 years of the GDR regime, and it remains an important, if somewhat unsightly, cultural landmark in the city today.

The opera house was designed in the socialist modernist (aka socialist realist) style that was prevalent in East Germany and elsewhere in the Soviet controlled territories of East and Central Europe during the 1950s and 1960s. Monumentality, uniformity, a functional design and simplicity are all key characteristics of the style, one you can see embodied not only in the opera house in Leipzig but also in the Palace of the Parliament in Bucharest, the Stadthalle in Chemnitz (formerly Karl-Marx Stadt) and the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw.

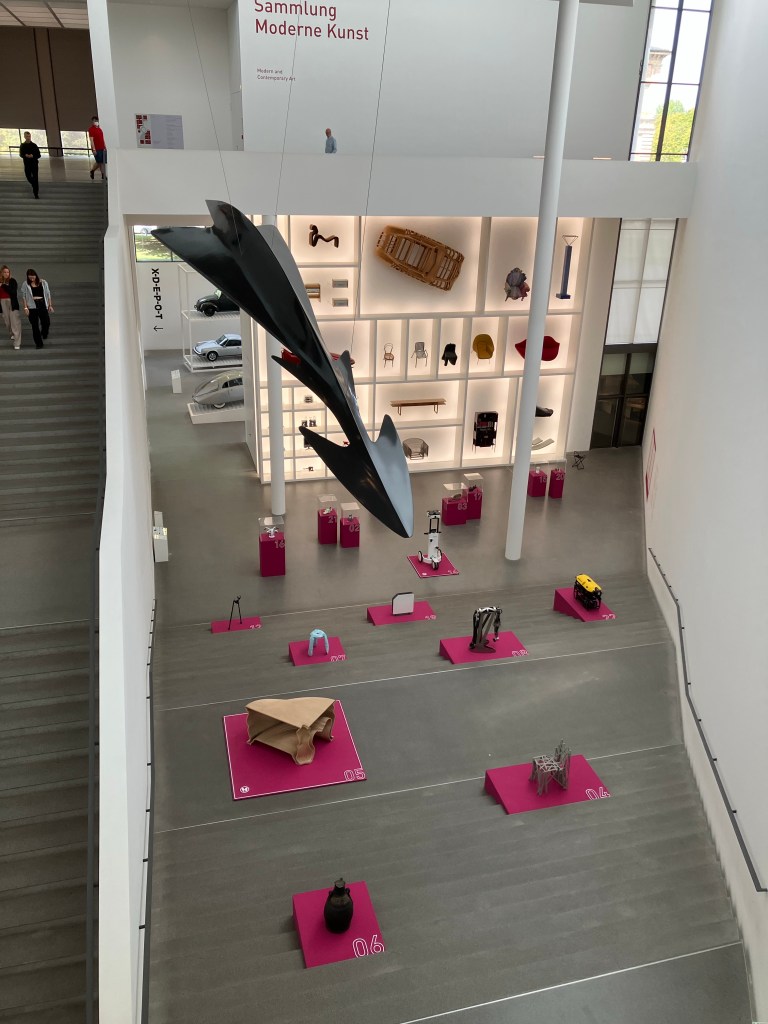

Leipzig declined as a city during the Communist years but is now very much on the up, especially with the young and creative who are flocking to a city dubbed the ‘new Berlin’ for its arts scene, cheap rents and overall ‘vibe’. To date it has avoided obvious gentrification with the negatives that process entails although how long the city can avoid the pitfalls of ‘hip’ popularity which have befallen other cities.

In particular, the city’s local authority has been especially supportive of the arts and it has helped to create an environment where creativity and innovation can flourish by providing funding and resources to help transform former industrial sites into creative hubs. It has also encouraged the development of new art galleries and exhibition spaces. As a result, the city is attracting artists from all over Germany and elsewhere in Europe with its affordable studio space. In particular, the Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei is especially noteworthy in this respect. It is a 10-hectare industrial site in the city’s Lindenau district where over 100 artists’ studios and eleven galleries and exhibition spaces, with approximately 120 independent artists creating their work on the site. Resident artists pay rent to have a studio or exhibition space at the Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei. The rents are comparatively low with some paying around 200 Euros per month for a shared studio. Other noteworthy creative spaces include the Taptenwerk, with its mix of galleries, workshops, Westwerk with its artist’s studios and Monopol, the former liqueur warehouse which now houses painters, actors, musicians with it’s pertinent motto of ‘leben, kunst and gutes karma’ (‘love, art and good culture’). Leipzig seems to be avoiding (at least for the present) the fate which has befallen other former creative hot spots such as London and New York when the onset of gentrification is so advanced, only the wealthy can afford to live in formerly bohemian neighbourhoods, where your neighbours are no longer writers per se but copywriters.

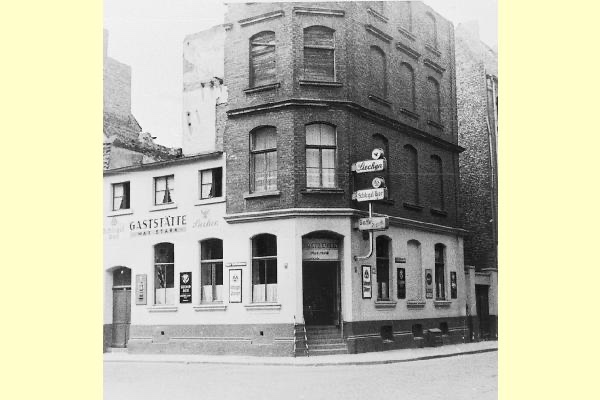

Alongside its art scene, Leipzig is home to a proud coffee house culture which, although far less vibrant than a city like Vienna, are still great places for both a kaffee and. Leipziger Lerche, a ubiquitous treat in the city of shortcrust pastry filled with crushed almonds, nuts and strawberry jam. Although Bach’s favourite coffee house in the city, Cafe Zimmermann (where several of his work including the Coffee Cantata were first performed) is no more, there are still around 11 popular cafes and coffee roasteries in the city.

Our favourite coffee house is the Cafe Riquet in the centre of Leipzig, standing as it does between car parks. The surrounding area, like much of Leipzig, was heavily bombed during World War II. The cafe itself suffered significant damage, with large parts of the pagoda and first floor being burnt. However, the building was able to survive the war, and was eventually restored to its former glory.

The original Cafe Riquet in Leipzig was founded in 1745 by a French Huguenot named Jean George Riquet. He established Riquet & Co, a company that specialized in importing exotic items like tea, coffee, and chocolate. The owner later included a public coffee dispenser and the cafe grew from that. The current building, with its two elephant sculpture heads flanking the entrance, was built in 1908. The interior features ornate wooden carvings, vintage furniture and wooden panels that create a warm atmosphere and a place to linger, especially on a cold day.

The café is known for its speciality coffee (variously Kaffee Riquet, Elefantenkaffee, and Pharisäer) and cakes, including, of course the Leipziger Lerche.

Food wise, whilst you can eat well in Leipzig (and the city has no shortage of Munich style beer halls), overall other German cities we have visited recently (e.g. Kőln, Hamburg and Munich) have a far more diverse restaurant scene in our opinion.

Still, if you want a schnitzel and a beer…..