An old city, dating back to the 10th century, Gdańsk suffered almost total destruction during WW2. The city’s subsequent reconstruction and most importantly, the crucial part it played in the Solidarity movement of the 1980’s means that today, Gdańsk is the third most visited city in Poland after Warsaw and Kraków and it is deservedly viewed by the rest of the country as an independent minded and resilient cultural hotspot.

The city we came to know starts after 1945. The destruction of Gdańsk during WWII was devastating. The centre of Gdańsk was 95% destroyed, with extensive damage from bombing and shelling.

After the war, the city was rebuilt from the ground up, thanks to the efforts of several generations of Polish people. Reconstruction took more than 70 years and continues to this day. As with the old town in Warsaw (levelled in an act of wanton vindictiveness by the Nazi’s after the Warsaw uprising), the older parts of Gdańsk were rebuilt according to the way the city was before WW2. During the rebuilding, a variety of historical records were consulted to ensure that the city was reconstructed as faithfully as possible. Artisans and architects were brought in to recreate the Old Town in its historical form by using traditional methods and materials.

Today the Old Town is a UNESCO World Heritage site and it is one of Europe’s best historic centres. Whilst Gdańsk is very much a modern, forward thinking Polish city, the past is still a dark shadow. It is hard to overstate the sheer ruin brought on the country during WW2 and thereafter The most immediately destructive era, the years 1939 -1945 with the invasion of Poland by both Nazi and Soviet forces, the eventual rout of the former and the re-occupation of the country by the latter is brilliantly detailed within the city’s Museum of the Second World War (‘Muzeum II Wojny ŚwiatoweItj’) which opened in 2017, making it a relatively new addition to Gdańsk’s cultural landscape.

Visitors to the museum can expect to learn more about the events that led up to the war, as well as its impact on Poland and the rest of the world. Of particular note in our opinion, are the re- creation of a typically Polish family apartment before, during and after the Nazi occupation (and to follow, Soviet rule), with the rooms changing as the war and Nazi and Soviet occupations progressed. The exhibition is especially for children under the age of 12, taking them on a journey through time, exploring different moments and events during World War II including the recreation of a typical pre – war Polish schoolroom. The museum’s website at https://muzeum1939.pl/en describes this most important exhibit as follows:-

The first exhibit is a reconstruction of a Warsaw family’s apartment during three different periods: September 3rd, 1939 – a few days after the outbreak of World War II, March 8th, 1943 – during the German occupation, and May 8th, 1945 – on the day of Germany’s surrender. These interiors show the living conditions of a well-educated Polish family from Warsaw. The changing elements of the interior decor reflect the shifting political, social and economic situation of the occupied country during the fighting. The exhibition is designed to make visitors aware of the deteriorating living conditions from year to year, the difficulties with food supplies, the rules imposed by the occupants, as well as the methods of coping with these difficulties. The exhibition also focuses on showing the attitudes of family members, describing their involvement in anti-German activities and civil forms of resistance – including the secret underground education of children. An important thread in the story is also the fate of the Jewish population, exemplified by the fate of the family’s pre-war Jewish neighbours. The journey through the occupation years takes place with the Jankowski family of four. To create this history, typical elements taken from wartime biographies of Polish intellectuals were used.

The museum is located very near to the Polish Post Office which played a significant role during the beginning of World War II. On September 1, 1939, at the start of the German invasion of Poland, the Post Office in was attacked by German police and SS units. At the time, the Post Office was a Polish enclave in the predominantly German-populated Free City of Danzig (now Gdańsk). The Polish employees at the Post Office, numbering around 50, were members of the Polish Military Transit Depot and were considered a threat by the Germans. They defended the Post Office against the German attack. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the Polish defenders held out for nearly 15 hours.

The defenders of the Post Office finally surrendered after the Germans brought in heavier weapons and set the building on fire. Six people were killed during the battle, and the survivors were arrested and put on trial. Despite their status as combatants, they were sentenced to death for illegally using weapons. All but four of the sentences were later commuted to life imprisonment, and the remaining four were executed.

The defence of the Polish Post Office in Gdańsk has become a symbol of Polish resistance against the German invasion and the beginning of World War II. Today, a monument stands in front of the Post Office building to commemorate the heroic actions of its defenders as well as related graffiti art murals on near by walls.

The defence of the Post Office is featured in Chapter 18 of The Tin Drum by the German author, Günter Grass, a native of Gdánsk or rather Danzig as it was known when the city was annexed by Germany. His literary work, and in particular, The Tin Drum, the first part of his Danzig Trilogy (‘Cat and Mouse’ and ‘Dog Years’ were to follow) certainly brought the city and it’s post 1925 history to the world’s attention.

The Tin Drum is a story about a boy named Oskar Matzerath, who refuses to grow up and wills himself to remain a child. Born in the early 20th century in the city of Danzig (Gdańsk), Oskar is a witness to the rise of Nazism and the horrors of World War II.

The story begins with Oskar’s birth and his refusal to leave the womb until his mother promises him a tin drum. On his third birthday, he decides to stop growing and throws himself down the stairs, using his tin drum as a weapon against the chaos around him.

“I will not grow, I will not grow, I will not grow. I will stay in Danzig, I will stay with my tin drum, I will stay a child forever.”

As Oskar grows older, he remains physically a child but develops a sharp intellect and a unique perspective on the world. He becomes an observer of the hypocrisy and injustice around him, using his drumming and screaming as a form of protest, especially against the stupidity and ugliness of the Nazi’s and their supporters.

Throughout the novel, Oskar interacts with a range of characters, including his family, friends, and various figures in the city of Danzig. He witnesses the rise of the Nazi party, the increasing violence against outsiders, and the eventual destruction of his hometown.

In the end, Oskar ends up in a mental institution, where he recounts his life story. Through his narration, Grass offers a powerful critique of war and the impact it has on individuals and communities.

There are several memorials and tributes to Günter Grass in Gdansk including an art Gdansk gallery dedicated to his work, a monument to Grass in the district where The Tin Drum was set and perhaps most famously, the Little Oskar statue, commemorating Grass’s most famously work and literary character. That statue is part of a larger monument called “Oskar’s Bench”, ocated in plac Generała Józefa Wybickiego in Gdańsk. The statue depicts Gunter Grass sitting on a bench opposite a statue of Oskar. The two figures appear to be in conversation or alternatively, Grass is reading to Oskar from the book on his lap. The book has a snail crawling across it, a reference to another of Grass’s works, “From the Diary.”

The novel remains the best known work by Günter Grass and it is one of the most celebrated works in the German language.

The film adaptation of the novel by acclaimed German director Wim Wenders, released in 1979, stays true to the novel’s plot and themes, featuring a remarkable performance by the actor David Bennent as Oskar. It was a critical success, winning the Palme d’Or at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1980.

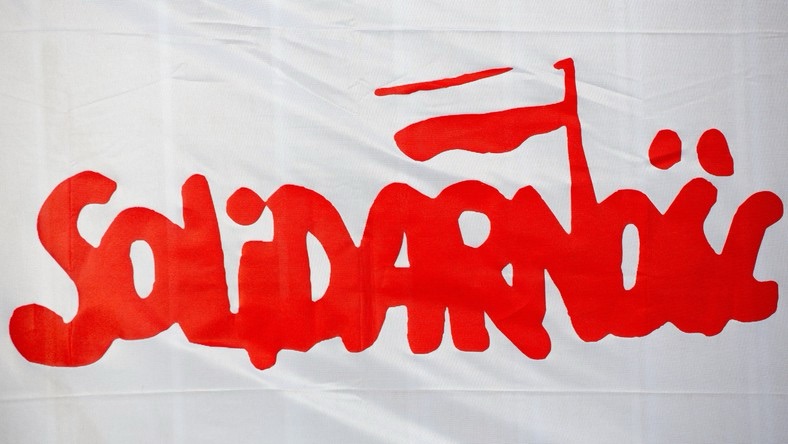

Gdańsk is home to another iconic museum which, like the Museum of the Second World War, documents remarkable events in the city and Poland’s recent history. The Museum in question is the Solidarity Museum, also known as the European Solidarity Centre. It is dedicated to the history of the Solidarity movement, a Polish trade union and civil resistance organisation that played a pivotal role in the country’s struggle for democracy and workers’ rights during the communist era.

Situated in the northern part of the city, adjacent to the Gdańsk shipyard (‘ Stocznia Gdańska in Polish, formerly known as the Lenin Shipyard), the Museum opened in 2014. Its design, by Polish firm FORT Architects, was inspired by the hulls of ships built at the Gdańsk Shipyard, where the Solidarity (“Solidarność”) trade union movement was born in 1980. The movement was created when the Communist government of Poland signed an agreement allowing for the creation of independent trade unions. The charismatic Lech Wałęsa, a labor activist, was instrumental in the formation of Solidarity and became its chairman. The union quickly gained popularity and represented most of the Polish workforce, with a membership of about 10 million people.

Solidarity advocated for economic reforms, free elections, and the involvement of trade unions in decision-making processes. The union’s growing influence led to a series of controlled strikes in 1981, pressuring the government to negotiate. However, the Polish government, under pressure from the Soviet Union, eventually suppressed the union and imposed martial law.

Despite being forced underground, Solidarity continued to operate as an illegal organisation until 1989 when the government recognised its legality. In the 1989 national elections, Solidarity candidates won most of the contested seats in the assembly and formed a coalition government. The union played a significant role in the fall of communism in Poland and the transition to a free market economy.

Lech Wałęsa’s leadership and determination were crucial in the formation and perseverance of Solidarity. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983 for his efforts and is considered a symbol of the struggle for freedom and democracy in Poland and throughout Eastern Europe.

Solidarity was the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country and quickly grew into a broad, non-violent, anti-Communist social movement. It played a significant role in the fall of communism in Poland and beyond.

The Solidarity movement is clearly documented and celebrated in the city’s Solidarity Museum, also known as the European Solidarity Centre.

Exhibits at the Museum include the original boards with the 21 demands of the Solidarity movement, which are included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. Other exhibits feature dioramas and props that recreate the economic hardships of Poland in the 1980s, slideshows and film reels that document political uprisings and the imposition of martial law, and interactive displays that tell the stories of the individuals who shaped the movement.

As the leader of the movement, Lech Walesa is obviously the most prominent figure in the Solidarity museum and the Museum’s exhibitions depict Walesa as a hero of the movement, highlighting his role in leading the strikes at the shipyard. which led to the formation of Solidarity.

After Poland became independent, Walesa continued to play a significant role in Polish politics. He served as the country’s first democratically elected president from 1990 to 1995, and he remains an important figure in Polish history and a symbol of the struggle for freedom and democracy.

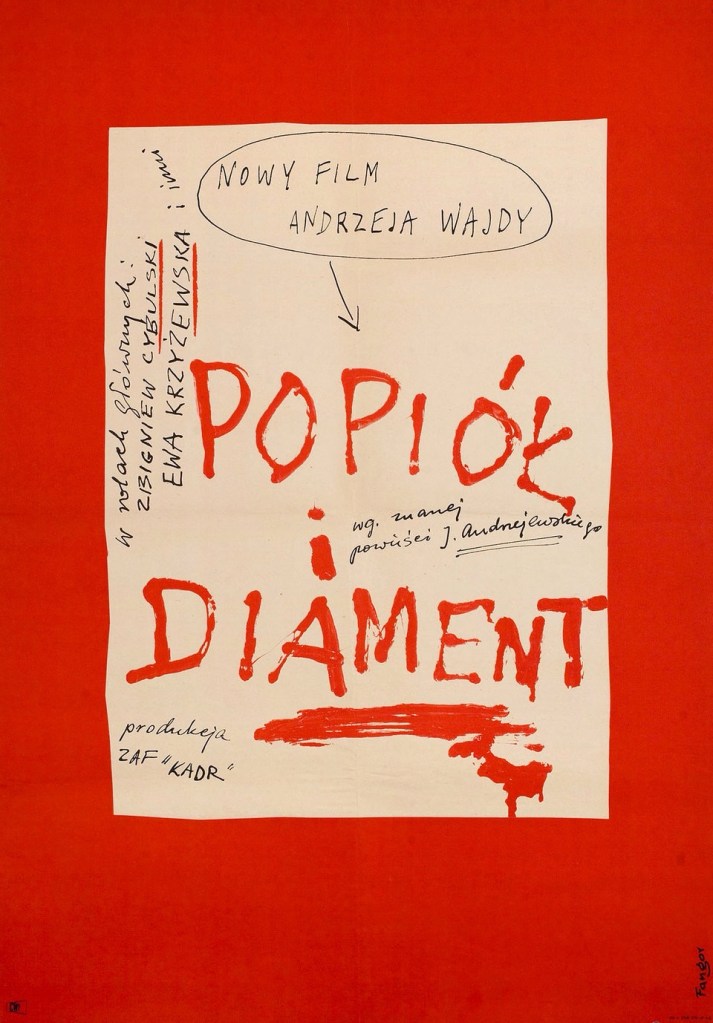

Another important figure in Poland was the Film Director, Andrzej Wajda. Often referred to as the “Father of Polish cinema” or the “Father of the Polish Film School” he directed a number of films that engaged with contemporary Polish history. With his work internationally recognised and he won numerous plaudits on the world stage including an Academy Award for lifetime achievement in 2014 (presented by Jane Fonda no less).

Andrzej Wajda made several films that dealt with the Solidarity movement, the most prominent of which is “Man of Iron” (1981). This film tells the story of a young Polish worker named Maciej Tomczyk, who becomes involved in the Solidarity movement and the struggle for workers’ rights in Poland in the early 1980s and it was made during a time of political upheaval in Poland. Its release coincided with the government’s crackdown on the Solidarity movement. Lech Walesa is featured prominently in the film.

Wajda also made several films about World War II, including his famous “War Trilogy,” which consists of “A Generation” (1955), “Kanal” (1957), and “Ashes and Diamonds” (1958). These films are considered classics of Polish cinema and deal with different aspects of the war and its impact on Polish society.

In “A Generation,” Wajda explores the experiences of young people living under Nazi occupation in Warsaw, while “Kanal” follows a group of Polish resistance fighters as they try to escape the city through the sewers during the Warsaw Uprising. “Ashes and Diamonds,” meanwhile, takes place in the aftermath of the war and deals with the complex political situation in Poland as the country begins to rebuild.

Wim Wenders paid tribute to Andrzej Wajda at the European Film Awards (EFA) in 2016. Wenders spoke warmly of Wajda’s contributions to cinema, highlighting the importance of truth, freedom, and solidarity in his work. Wajda had previously been awarded a lifetime achievement award by the EFA in 1990. Wenders was awarded the same recognition by the EFA in 2024.

(The European Film Awards (EFA) is an annual awards ceremony of the European Film Academy which is dedicated to promoting the interests of the European film industry on the world stage).

‘’Gdansk is a city that has always been at the forefront of social and political change, and that is something that I have tried to capture in my films.”

Andrzej Wajda