Lampião, o Rei do Cangaço

The Sertão is the name given to the vast arid hinterland of the North East of Brasil. Notable for its semi-arid conditions, poverty, cactus and scrub, the North East in general has had a vivid and important impact on Brasilian popular history and culture including of course the legend of Lampião, ‘O Rei do Cangaço’.

The Sertão was home to the ‘cangaços’, gangs of bandits who roamed the backlands of the North East in the earlier part of the last century attacking landowners and stealing from the wealthy in particular. They were known for their ferocity towards those they robbed and plundered as well as their apparent generosity towards the poor, despite widespread torture and murder of their victims. It is this role as ‘social bandits’ rather than as wild outlaws that the cangaçeiros are best remembered in modern day Brazil. The best known of the cangaceiros was Virgulino Ferreira da Silva, known to everyone as ‘Lampião’. Together with his girlfriend and fellow gang member Maria Déia aka ‘Maria Bonita’ (‘Pretty Maria’) they roamed the Brazilian backlands with the gang from the 1920’s until their deaths in 1938, four years after the deaths of their counterparts in the US, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, ‘Bonnie and Clyde’. Just like that Texan couple, Lampião and Maria would be eulogised in film and song across the ages.

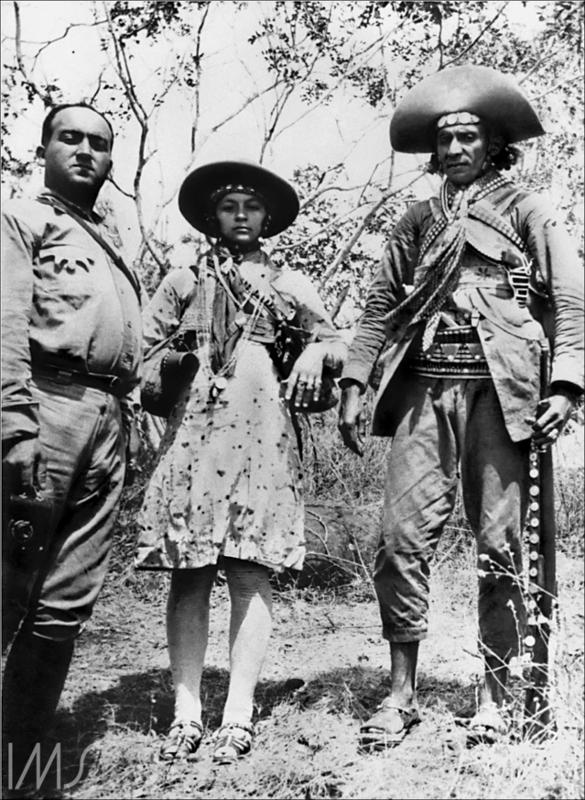

The first (and most interesting) film about Lampião and his gang (‘Lampião, o Rei do Cangaço’ – ‘Lampião, the King of the Bandits’) was made in 1937 by Benjamin Abrahão. He had been born in Lebanon but later moved to Brasil. He met Lampião in 1926 via Cícero Romão Batista aka ‘Padre Cícero’, the spiritual leader to the people of the North East of Brazil. A legendary figure in his own right, Padre Cícero was highly trusted by the deeply religious Lampião who he persuaded to allow Abrahão to meet and photograph the gang. Although very cautious, Lampião was intrigued by the possibility of meeting Abrahão, being photographed and having the chance to more widely publicise his highly stylised gang. Lampião was already image concious by this time, handing out business cards and images of the gang to admirers.

Abrahão initially took photographs of a suspicious Lampião and his wary band and then when trust had been established, filmed them out in the Sertão. The resulting silent film ‘O Rei do Cangaço’ was originally two hours long but only less than 15 minutes of film stock remains.

The film was a great success upon its release. in Brasil but it was soon seized under the directions of the then President Getúlio Vargas and it more or less disappeared from view until 1955 when its remaining stock was restored and released nationwide, the film being only ten minutes long. Then in 2007, Cinemateca Brasileira (the national organisation responsible for the restoration and distribution of important audio visual material) restored and re-edited the available film stock and organised the release of some 14 minutes of film. It is this version, O Rei do Cangaço by Benjamin Abrahão, which can be seen on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmqd-ijH2cQ.

At a makeshift camp in the harsh Sertão the cangaçeiros are seen resting, using a sewing machine, praying at a makeshift altar, skinning and eating a cow and undertaking a mock skirmish etc. Lampião is clearly visible as is another key member of the gang, the cruel Corisco. Maria Bonita is filmed combing Lampião’s hair in one scene.

At least two women are seen with the gang in the film including Maria Bonita, Lampãio’s girlfriend as well as Dadá, the lover of Corisco. The film maker Benjamin Abrahão is also clearly visible in some scenes, eating and drinking with the gang.

The Cangaceiros are also seen dancing in the film. The dance most closely associated with the gang is the Xaxado, a popular North Eastern style which is still performed today.

Abrahão’s photographs and film helped fix the stylised image of Lampião and the cangaceiros in Brasilian popular culture.

Each member is wearing leather outfits of a hat, jacket and jodhpurs/shirts tough enough to protect them from the thorns of the caatinga (dry shrubs and brushwood typical of the dry hinterland of the Sertão). Studded ammunition belts criss cross eash chest. The hats are half moon shaped and decorated with metals stars, fleur de lis, maltese crosses and other designs. The rifle slings are studded with silver coins and highly decorated cloth bags are draped from each shoulder. Long neckerchiefs tied with a silver rings are draped around each neck. Dark glasses are sometimes worn. The effect is startling and original and whilst the alleged ‘Robin Hood’ nature of the gang will no doubt have assisted in creating the Lampião myth, one cannot help but feel that its overall strong visual aesthetic contributed as great an impact to its ultimate longevity and influence in the popular imagination. We can see this in the culture of Zoot suits in Los Angeles in the 1940’s, the startling images of the Sex Pistols in 1970’s London (in clothes by the ground breaking Seditionaries) and the elevated dress sense of the Sapeurs of the Congo.

The strongest influences on popular culture, whether in Brasil or elsewhere, do not come from the elite. As the English writer V.S. Pritchett once commentated noted, ”the past of a place survives in its poor.” Although this comment was made by following his travels in Spain it applies elsewhere, no more so than Brasil with its reverance of the legend of Lampião.

Visit the North East of Brasil and referances to Lampião and his gang are ubiquitos. Whether in popular songs and films, the names of restaurants and bars to the classic woodcut prints of the Borges family, the cangaço and his gang are everywhere.

As a postscript to the film (which views like an epitaph), both Lampião and Maria Bonita were cornered shortly thereafter by bounty hunters and killed with nine other members of the gang. They were then decapitated, their heads were put on public display in the city of Piranhas in the North East state of Alagoas (the city had been attacked several times by Lampião and his gang) before ending up at the State Forensic Institute in Salvador, Bahia where they remained until burial in 1969. A graphic photograph of the severed heads surround by decorated hats, weapons, bags and bandoliers, framed by two sewing machines is readily visible on the internet but it is not exhibited here.

Two other members of the gang, Corisco and his girlfriend Dadá, were amongst those who escaped but were cornered by the authorities not long thereafter. Corisco was killed in the attack and Dadá lost a leg from her wounds. She survived until her death in 1994, the last member of the gang to die.

With the deaths of Lampião and Corisco the phenomenon of cangaço, died out.

Filmmaker Glauber Rocha who spearheaded Brazil’s Cinema Novo in the early 1960’s was inspired by the story of Corisco and Dadá and featured representations of them in his ground breaking 1964 film Deus e o Diablo na Terra do Sol (known as ‘Black God, White Devil’ in English – you can see an old print of this film here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyTnX_yl1bw). Just like the much romanticised Lampião and Maria Bonita, Corisco and Dadá became Bonnie and Clyde type figures in the Brazilian popular imagination and culture.

The filmmaker Benjamin Abrahão was brutally murdered shortly after the films initial release. His assailant was never found. The film was seized by the authorities who did not approve of the fact that the film did not condemn the gang and its activities. Lampião and his gang were public enemies No. 1 for Vargas and his presidency.